Strawberry Fields Forever

The Beatles recorded two more takes of Strawberry Fields Forever, numbered 5 and 6, during this 2.30-8pm session.

The group began with lengthy rehearsals and discussions, before recording take 5. The performance was a false start, however, but take 6 was successfully performed through to the song's close.

The Beatles used the same arrangement as the previous day's session, with a rhythm track featuring Paul McCartney on Mellotron, John Lennon and George Harrison on electric guitars, and of course, Ringo Starr on drums.

Take 6 was a strong performance with an extended coda. Lennon added slowed down vocals and McCartney recorded a bass guitar part, and a reduction mix was made to free up two tracks on the tape. This mix became take 7.

John Lennon then double-tracked his vocals during the choruses, and an overdub using the Mellotron's guitar and piano settings was the last item to be recorded. Three rough mono mixes, numbered 1-3 were then made and four acetate discs were pressed for The Beatles' reference.

The group later remade the song, but the first minute of take 7 was eventually incorporated into the final release.

Studio Two, EMI Studios, London

The Beatles recorded three more takes of Strawberry Fields Forever during this 7pm-1.30am session.

The Beatles' first task was to complete a satisfactory rhythm track. Take two followed a similar arrangement to the first session's, with a Mellotron introduction performed by Paul McCartney, John Lennon and George Harrison on electric guitars, and Ringo Starr on drums and maracas. It ended after the final chorus.

Take three broke down during the introduction, after Lennon complained that the Mellotron was too loud. The fourth take was complete, however, and featured Harrison using the Mellotron's guitar setting to add slide guitar and Morse code-style notes. Lennon then added lead vocals, with the tape running faster so it was slower upon playback, and McCartney added a bass guitar part to the final track.

Take four was marked 'best', albeit temporarily. Three rough mono mixes were then made for reference purposes, but after further reflection, The Beatles decided to re-record the rhythm track on the following day.

Broadwick Street, London

Lennon played the role of Dan, a doorman at the fictional nightclub Ad Lav. The name was a spoof on the Ad Lib Club, a venue often frequented by The Beatles and other leading showbusiness personalities of the mid-1960s. Dan the doorman

Lennon wore a uniform complete with top hat and gloves, and for perhaps the first time in public wore the wire-framed granny glasses that would soon become his trademark.

The 51-second sketch was filmed early in the morning on London's Broadwick Street, beside the entrance to the underground men's toilet on the corner of Hopkins Street. It also featured Peter Cook as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor.

Strawberry Fields Forever was one of The Beatles' most complicated recordings. With George Martin they spent some time working on the arrangement, going through various re-makes and spending an unprecedented 55 hours of studio time completing the song.

The Beatles' fourth Christmas record, Pantomime: Everywhere It's Christmas, was recorded on this day at the first floor demo studio owned by their publisher, Dick James.

Each member of The Beatles sang on the recording, with Paul McCartney also playing piano. A number of songs and skits were recorded, which were edited into a 10-part, six-minute piece on 2 December. The songs included Everywhere It's Christmas, Orowainya, and Please Don't Bring Your Banjo Back, and the sketches included Podgy The Bear And Jasper, and Felpin Mansions.

The Beatles' Fourth Christmas Record – Pantomime: Everywhere It's Christmas was edited by The Beatles' press officer at Abbey Road on December 2, 1966, and was sent to members of The Beatles' UK fan club on December 16th.

Studio Two, EMI Studios, London

And so the beatles entered the new phase of their career! No longer the tidy, smiling "Fab Four", singing boy/girl pop songs on stage. Now they were the casually dressed, sometimes mustacioed, not always smiling Beatles who would make the greatest ever batch of rock recordings at and for their merest whim, strictly not for performing on stage.

John, Paul, George and Ringo had scarely spent a day together since early September. Now they had decided to reunite and begin recording a new album. "Strawberry Fields Forever" captured in one song much of what the Beatles had learned in the four years spent inside recording studios, and especially 1966, with its backwards tapes, vari-speeds and uncommon musical instruments. And it could only have been born of a mind (John Lennon's) under the influence of outlawed chemicals. Strawberry Field is a Salvation Army home in Liverpool, around the corner from where John was brought up. He went there for summer fetes and had called the surrounding wooded area Strawberry Fields. "Strawberry Fields Forever" evoked those childhood memories through a dreamy, hallucinogenic haze. It was, and remains, one of the greatest pop songs of all times.

It is also known, correctly, for being among the most complicated of all Beatles recordings, changing shape not once but several times. Take one, recorded from 7:00 pm to 2:30 am in this first session, was certainly far removed from the final version, the only similarity being a mellotron introduction. (The precursor of the synthesier, this instrument contained tapes which could be "programmed" to imitate another instrument, in this instance a flute.) By 2:30 am take one sounded like this: simultaneous with the mellotron, played by Paul, was John's first lead vocal, followed by George's guitar, Ringo's distinctive drums (with dominant use of tomtoms), maracas, a slide guitar piece, John's double-tracked voice and scat harmonies by John, Paul and George. The song came to a full-ending with the mellotron. The entire take was recorded at 53 cycles per second so that it sped up on replay, but still it lasted only 2 minutes, 43 seconds.

Source: The Complete Beatles Chronicle - Mark Lewisohn

Leonard Bernstein, who took an ongoing interest in the Beatles, analyzes the harmonic structure of "Norwegian Wood" in the televised Young People's Concert, "What is a Mode?"

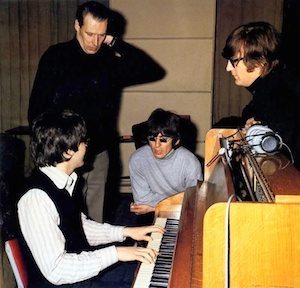

The Beatles are getting ready to record a very famous tune. Can anyone guess?

Nothing to mention on this day 50 years ago.

The Four Tops had performed at the Savile Theatre in London on 13 November 1966. The venue was owned by The Beatles' manager Brian Epstein, and the backdrop for the performance was said to have been designed by Paul McCartney.

Seven days later Epstein held a party for The Four Tops at his home at 24 Chapel Street, London. It was attended by John Lennon and George Harrison.

Paul McCartney had flown to France on November 6, 1966 and met Mal Evans in Bordeaux on November 12 before flying to Kenya for a safari holiday.

In Kenya they were joined by McCartney's girlfriend Jane Asher, and the three of them visited the Ambosali Park at the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro, and stayed at the Treetops Hotel in Aberdare National Park.

They spent their final night on 18 November at the YMCA in Nairobi before flying back to London on this day. During the flight McCartney had the idea for Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

We were fed up with being the Beatles. We really hated that fucking four little mop-top boys approach. We were not boys, we were men. It was all gone, all that boy shit, all that screaming, we didn't want any more, plus, we'd now got turned on to pot and thought of ourselves as artists rather than just performers. There was now more to it; not only had John and I been writing, George had been writing, we'd been in films, John had written books, so it was natural that we should become artists.

Then suddenly on the plane I got this idea. I thought, Let's not be ourselves. Let's develop alter egos so we're not having to project an image which we know. It would be much more free. What would really be interesting would be to actually take on the personas of this different band. We could say, 'How would somebody else sing this? He might approach it a bit more sarcastically, perhaps.' So I had this idea of giving the Beatles alter egos simply to get a different approach; then when John came up to the microphone or I did, it wouldn't be John or Paul singing, it would be the members of this band. It would be a freeing element. I thought we can run this philosophy through the whole album: with this alter-ego band, it won't be us making all that sound, it won't be the Beatles, it'll be this other band, so we'll be able to lose our identities in this.

Me and Mal often bantered words about which led to the rumour that he thought of the name Sergeant Pepper, but I think it would be much more likely that it was me saying, 'Think of names.' We were having our meal and they had those little packets marked 'S' and 'P'. Mal said, 'What's that mean? Oh, salt and pepper.' We had a joke about that. So I said, 'Sergeant Pepper,' just to vary it, 'Sergeant Pepper, salt and pepper,' an aural pun, not mishearing him but just playing with the words.

Then, 'Lonely Hearts Club', that's a good one. There's lot of those about, the equivalent of a dating agency now. I just strung those together rather in the way that you might string together Dr Hook and the Medicine Show. All that culture of the sixties going back to those travelling medicine men, Gypsies, it echoed back to the previous century really. I just fantasised, well, 'Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band'. That'd be crazy enough because why would a Lonely Hearts Club have a band? If it had been Sergeant Pepper's British Legion Band, that's more understandable. The idea was to be a little more funky, that's what everybody was doing. That was the fashion. The idea was just take any words that would flow. I wanted a string of those things because I thought that would be a natty idea instead of a catchy title. People would have to say, 'What?' We'd had quite a few pun titles - Rubber Soul, Revolver - so this was to get away from all that.

The Beatles began recording the Sgt Pepper title track on February 1, 1967.

Nothing newsworthy today. What do you think the Beatles were doing?

Nothing much happened to make the news this day 50 years ago.

Moustaches were catching like the flu- not only do the Fab Four grow them, Beatles assistants Mal Evans and Neil Aspinall grow 'em to.

The Beatles each doing their own thing today.

Nothing notable happened on this day 50 years ago.

One week after beginning his road trip across France, Paul McCartney had a rendezvous with The Beatles' roadie Mal Evans in Bordeaux.

Prior to meeting Evans, McCartney spent the night in a Bordeaux club. Wearing the moustache and glasses disguise he had prepared to allow him to travel incognito, the club staff wouldn't let him in.

I looked like old jerko. 'No, no, monsieur, non' - you schmuck, we can't let you in! So I thought, Sod this, I might as well go back to the hotel and come as him! So I came back as a normal Beatle, and was welcomed in with open arms. I thought, Well, it doesn't matter if I've blown my cover because I'm going to meet Mal anyway, I don't have to keep the disguise any longer. Actually, by the time of the club I'd sort of had enough of it. Which was good. It was kind of therapeutic but I'd had enough. It was nice because I remembered what it was like to not be famous and it wasn't necessarily any better than being famous.It made me remember why we all wanted to get famous; to get that thing. Of course, those of us in the Beatles have often thought that, because we wished for this great fame, and then it comes true but it brings with it all these great business pressures or the problems of fame, the problems of money, et cetera. And I just had to check whether I wanted to go back, and I ended up thinking, No, all in all, I'm quite happy with this lot.

McCartney met Evans at the Saint-Eloi catholic church, on Rue Saint-James in Bordeaux.

We met up, exactly as planned, under the church clock. He was there. I figured I'd had enough of my own company by then. I had enjoyed it, it had been a nice thing. Then we drove down into Spain but we got to Madrid and we didn't know anyone; the only way would have been to go to a club and start making contacts. So we thought, This is not going to be any fun, and rang the office in London, and booked ourselves a safari trip.

The pair drove from Bordeaux to Spain, making films on their journey. They had hoped to meet John Lennon in Almería, but filming for How I Won The War had ended and he had returned to England.

Instead they decided on a safari holiday and flew to Kenya. McCartney arranged to meet his girlfriend Jane Asher there, and in Seville had someone drive his Aston Martin DB5 back to London.

McCartney and Evans flew from Seville to Madrid, and from there to Nairobi. They had a 10-hour stopover in Rome, during which they did some sightseeing.

Upon their arrival in Kenya they toured Ambosali Park, overlooked by Mount Kilimanjaro, and stayed at the Treetop Hotel, the royal family's Kenyan base. The holiday came to a close on 19 November, when McCartney, Asher and Evans flew from Nairobi back to London.

The Beatles each busy on their own.

Room 65, EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Engineer: Peter Bown

This was the last of four mixing sessions to prepare stereo versions of Beatles songs ahead of the UK compilation album A Collection Of Beatles Oldies on December 9, 1966.

Once again George Martin was not present, so the session was led by balance engineer Peter Bown. The first song worked on was "This Boy", which was the result of a misunderstanding. During a telephone call from EMI's headquarters at London's Manchester Square, Bad Boy was mistakenly called This Boy.

This led to stereo mixes being made from takes 15 and 17, which were edited together towards the end of the session. They were unnecessary, however, and the stereo mix of Bad Boy from May 10, 1965 was used for the album.

Day Tripper was the second song to receive a stereo mix. This replaced an earlier one made on October 26, 1965 for The Beatles' US and Australian record labels.

The third and final song was "We Can Work It Out". A previous stereo mix had been created on November 10, 1965, but was crapped on August 9, 1966.

The 'Paul Is Dead' myth began in 1969, and alleged that Paul McCartney. The Beatles are said to have covered up the death, despite inserting a series of clues into their songs and artwork. The story goes that at 5am on Wednesday - 9 November 1966, McCartney stormed out of a session for the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album, got in to his Austin Healey car, and subsequently crashed and died.

Somewhat improbably, McCartney was said to have been replaced by a lookalike, called variously William Shears Campbell or William Sheppard. William Campbell allegedly became Billy Shears on Sgt Pepper, while William Sheppard was supposedly the inspiration behind "The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill" (actually an American named Richard Cooke III).

In fact, the crash never happened. Between 6 and 19 November 1966, McCartney and his girlfriend Jane Asher were on holiday, travelling through France and Kenya.

However, a couple of relevant incidents did take place. On December 26, 1965 McCartney crashed his moped, resulting in a chipped tooth and a scar on his top lip, which he hid by growing a moustache.

Additionally, on 7 January 1967 McCartney's Mini Cooper was involved in an accident on the M1 motorway outside London, as a result of which it was written off. However, the car was being driven by a Moroccan student named Mohammed Hadjij, and McCartney was not present.

Hadjij was an assistant to London art gallery owner Robert Fraser. The pair turned up at McCartney's house on the evening of 7 January, and were later joined by Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Brian Jones and antiques dealer Christopher Gibbs.

The party decided to head to Jagger's home in Hertfordshire, before moving on to Redlands, Richards' Sussex mansion (and scene of his later drugs bust). McCartney travelled with Jagger in the latter's Mini Cooper, while Hadjij drove in McCartney's Mini.

The two cars became separated during the journey. Hadjij crashed McCartney's Mini and was hospitalised with injuries. The heavily customised car was highly recognisable, so rumours began circulating that McCartney had been killed in the incident.

The following month a paragraph appeared in the February 1967 edition of the Beatles Book Monthly magazine, headed "FALSE RUMOUR":

Stories about the Beatles are always flying around Fleet Street. The 7th January was very icy, with dangerous conditions on the M1 motorway, linking London with the Midlands, and towards the end of the day, a rumour swept London that Paul McCartney had been killed in a car crash on the M1. But, of course, there was absolutely no truth in it at all, as the Beatles' Press Officer found out when he telephoned Paul's St John's Wood home and was answered by Paul himself who had been at home all day with his black Mini Cooper safely locked up in the garage.

Although the magazine downplayed the incident, and claimed the car was in McCartney's possession.

Belief that Paul McCartney may have died in the mid 1960s began in 1969. The first known print reference was in an article written by Tim Harper which appeared in the 17 September edition of the Times-Delphic, the newspaper of the Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa.

Harper later claimed that he wasn't the original source for any of the claims in his articles. He said he was writing for entertainment purposes only, and said he got the information from a fellow student, Dartanyan Brown. Mr Brown is said to have got the story from a musician who had heard it on the Californian west coast, and that he also read the story in an underground newspaper.

The rumours gained momentum on 12 October 1969, after an on-air phone call to radio presenter Russ Gibb, a DJ on WKNR-FM in Michigan. The caller, identified only as 'Tom', claimed that McCartney was dead, and instructed Gibb to play Revolution 9 backwards, where the repeated "number nine" phrase was heard as "turn me on, dead man".

Listening to the show was Fred LaBour, an arts reviewer for student newspaper The Michigan Daily. LaBour used clues from Gibb's programme along with others he had invented himself - including the name of William Campbell, the alleged replacement for McCartney.

The Michigan Daily published it on 14 October, under the title McCartney Dead; New Evidence Brought To Light. Although clearly intended as a joke, it had an impact far wider than the writer and his editor expected.

Shortly afterwards, Russ Gibb co-produced a one-hour special called The Beatle Plot, giving the rumour greater prominence; by then it was well on its way to become a national, then international, talking point, inspiring fans to pore over their albums for further clues.

A British version of the rumour is believed to have existed prior to the American one, with fewer details. The sources are unknown, but the notion of McCartney dying in a road accident appears to have originated there.

Although The Beatles and their press office at Apple were initially bewildered and somewhat annoyed by the story's refusal to die away, there is evidence that the group members themselves found it amusing.

In an edition of Life magazine dated 7 November 1969, McCartney reassured fans that "Rumours of my death have been greatly exaggerated," paraphrasing Mark Twain. "However," he continued, "if I was dead, I'm sure I'd be the last to know."

The magazine's cover featured Paul and Linda with their children, in a picture taken on their Scottish farm. The cover featured the words "The case of the 'missing' Beatle - Paul is still with us". Shortly after the issue went on sale the rumours started to decline.

In his revealing Rolling Stone interview in 1970, John Lennon was asked about the death story. He responded in a typically forthright fashion:

Lennon referred to the myth in 1971's How Do You Sleep?, his vitriolic attack on McCartney from the Imagine album. The song contains the lines: "Those freaks was right when they said you was dead, the one mistake you made was in your head".

McCartney parodied the rumours with the title and cover or his 1993 album Paul Is Live. The artwork was based on the Abbey Road cover photograph; instead of the 28IF number plate, a car shows 51 IS instead. To reinforce the cycle of life, he is pictured being dragged across the famous zebra crossing by one of the offspring of his sheepdog Martha.

Room 53, EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Engineer: Geoff

George Martin was not present for this third stereo mixing session for the UK compilation A Collection Of Beatles Oldies compilation, which was released on December 9, 1966, so balance engineer Geoff Emerick oversaw the work.

On the day before her exhibition Unfinished Paintings And Objects was to open, Japanese artist Yoko Ono was introduced to John Lennon for the first time.

John Lennon - That old gang of mine. That's all over. When I met Yoko is when you meet your first woman and you leave the guys at the bar and you don't go play football anymore and you don't go play snooker and billiards. Maybe some guys like to do it every Friday night or something and continue that relationship with the boys, but once I found the woman, the boys became of no interest whatsoever, other than they were like old friends. You know: 'Hi, how are you? How's your wife?' That kind of thing. You know the song: 'Those wedding bells are breaking up that old gang of mine.' Well, it didn't hit me till whatever age I was when I met Yoko, which was twenty-six. Nineteen sixty-six we met, but the full impact didn't... we didn't get married till '68, was it? It all blends into one bleeding movie!

But whatever, that was it. The old gang of mine was over the moment I met her. I didn't consciously know it at the time, but that's what was going on. As soon as I met her, that was the end of the boys, but it so happened that the boys were well known and weren't just the local guys at the bar.

The exhibition was held at the Indica Gallery, in the basement of the Indica Bookshop in Mason's Yard, just off Duke Street in Mayfair, London. The Indica was co-owned by John Dunbar, Peter Asher and Barry Miles, and was supported in its early years by Paul McCartney.

There was a sort of underground clique in London; John Dunbar, who was married to Marianne Faithfull, had an art gallery in London called Indica, and I'd been going around to galleries a bit on me off days in between records, also to a few exhibitions in different galleries that showed sort of unknown artists or underground artists.

I got the word that this amazing woman was putting on a show the next week, something about people in bags, in black bags, and it was going to be a bit of a happening and all that. So I went to a preview the night before it opened. I went in - she didn't know who I was or anything - and I was wandering around. There were a couple of artsy-type students who had been helping, lying around there in the gallery, and I was looking at it and was astounded. There was an apple on sale there for two hundred quid; I thought it was fantastic - I got the humor in her work immediately. I didn't have to have much knowledge about avant-garde or underground art, the humor got me straightaway. There was a fresh apple on a stand - this was before Apple - and it was two hundred quid to watch the apple decompose. But there was another piece that really decided me for-or-against the artist: a ladder which led to a painting which was hung on the ceiling. It looked like a black canvas with a chain with a spyglass hanging on the end of it. This was near the door when you went in. I climbed the ladder, you look through the spyglass and in tiny little letters it says 'yes'. So it was positive. I felt relieved. It's a great relief when you get up the ladder and you look through the spyglass and it doesn't say 'no' or 'fuck you' or something, it said 'yes'.

I was very impressed and John Dunbar introduced us - neither of us knew who the hell we were, she didn't know who I was, she'd only heard of Ringo, I think, it means apple in Japanese. And Dunbar had sort of been hustling her, saying, 'That's a good patron, you must go and talk to him or do something.' John Dunbar insisted she say hello to the millionaire. And she came up and handed me a card which said 'breathe' on it, one of her instructions, so I just went [pant]. This was our meeting.

Add Colour Painting featured white wood panels covered in cutout perspex, plus brushes and paints on a white chair. Visitors to the exhibition were invited to interact with the piece in whichever way they chose.

Yoko Onon - I call this Add Colour Painting. It is very important to have art which is living and changing. Every phase of life is beautiful; so is every phase of a painting.

Another piece was Play It By Trust aka White Chess Set, which carried the instructions: Play it for as long as you can remember who is your opponent and who is your own self. There was also Painting To Hammer A Nail In, a hammer attached to a block, into which people were invited to hammer nails.

John Lennon - Then I went up to this thing that said, 'Hammer a nail in.' I said, 'Can I hammer a nail in?' and she said no, because the gallery was actually opening the next day. So the owner, Dunbar, says, 'Let him hammer a nail in.' It was, 'He's a millionaire. He might buy it,' you know. She's more interested in it looking nice and pretty and white for the opening. That's why she never made any money on the stuff; she's always too busy protecting it!

So there was this little conference and she finally said, 'OK, you can hammer a nail in for five shillings.' So smart-ass here says, 'Well, I'll give you an imaginary five shillings and hammer an imaginary nail in.' And that's when we really met. That's when we locked eyes and she got it and I got it and that was it.

Lennon later recalled the date of their meeting as 9 November 1966, but this was after Ono's exhibition had opened. The most likely date is 7 November.

Having completed his work on the Richard Lester film How I Won The War, John Lennon returned to London on this day.

He had begun filming in West Germany, before flying to southern Spain to complete his scenes. Lennon played the role of Private Gripweed in the film, which was released in 1967.

He had been in Spain for seven weeks, initially staying at a small seafront apartment but later moving to a villa, Santa Isabel, near Almería. Lennon stayed at Santa Isabel with his wife Cynthia, and The Beatles' assistant Neil Aspinall. Also staying in the house was actor Michael Crawford, the star of How I Won The War, and his family.

On this day Paul McCartney flew to France on a plane-ferry from Lydd airport in Kent, England.

The intention was to take a driving holiday. In order to escape the attention of The Beatles' fans, McCartney wore a disguise, although his brand new dark green Aston Marton DB5 was enough to attract the attention of even the least observant bystander.

I was pretty proud of the car. It was a great motor for a young guy to have, pretty impressive said Paul McCartney

McCartney planned to drive to Paris before heading south to Bordeaux, where he had arranged to meet Mal Evans under the clock on the Saint-Eloi church on November 12, 1966. They then intended to follow the Loire river from Orleans.

It was an echo of the trip John and I made to Paris for 21st birthday, really. I'd cruise, find a hotel and park. I parked away from the hotel and walked to the hotel. I would sit up in my room and write my journal, or take a little bit of movie film. I'd walk around the town and then in the evening go down to dinner, sit on my own at the table, at the height of all this Beatle thing, to ease the pressure, to balance the high-key pressure. Having a holiday and also not be recognised. And re-taste anonymity. Just sit on my own and think all sorts of artistic thoughts like, I'm on my own here, I could be writing a novel, easily. What about these characters here in this room? - Paul McCartney

McCartney's journal was later lost, as was his film of his trip. Some of the reels were stolen by fans who broke into his home on Cavendish Avenue, London.

Kodak 8 mm was the one, because it came on a reel. Once it became Super-8 on a cartridge you couldn't do anything with it, you couldn't control it. I liked to reverse things. I liked to reverse music and I found that you could send a film through the camera backwards. Those very early cameras were great.

If you take a film and run it through a camera once, then you rewind it and run it through again, you get two images, superimposed. But they're very washed out, so I developed this technique where I ran it through once at night and only photographed points of light, like very bright reds, and that would be all that would be on the first pass of the film. It would be like on black velvet, red, very red. I used to do it in my car so it was car headlights and neon signs, the green of a go sign, the red of a stop, the amber.

The next day, when it was daylight, I would go and shoot and I had this film that was a combination of these little points of light that were on a 'black velvet' background and daylight. My favourite was a sequence of a leaning cross in a cemetery. I turned my head and zoomed in on it, so it opened just with a cross, bingo, then as I zoomed back out, you could see the horizon was tilted at a crazy angle. And as I did it, I straightened up. That was the opening shot, then I cut to an old lady, facing away from me, tending the graves. A fat old French peasant who had stockings halfway down her legs and was revealing a lot of her knickers, turning away, so it was a bit funny or a bit gross maybe. She was just tending a grave so, I mean, I didn't need to judge it. I just filmed it. So the beautiful thing that happened was from the previous night's filming. There she is tending a grave and you just see a point of red light appear in between her legs and it just drifts very slowly like a little fart, or a little spirit or something, in the graves. And then these other lights just start to trickle around, and it's like Disney, it's like animation!

One thing I'd learned was that the best thing was to hold one shot. I was a fan of the Andy Warhol idea, not so much of his films but I liked the cheekiness of Empire, the film of the Empire State Building, I liked the nothingness of it. So I would do a bit of that.

There were some sequences I loved: there was a Ferris wheel going round, but you couldn't quite tell what it was. And I was looking out of the hotel window in one French city and there was a gendarme on traffic duty. There was lot of traffic coming this way, then he'd stop 'em, and let them all go. So the action for ten minutes was a gendarme directing the traffic: lots of gestures and getting annoyed. He was a great character, this guy. I ran it all back and filmed all the cars again, it had been raining so there was quite low light in the street. So in the film he was stopping cars but they were just going through his body like ghosts. It was quite funny. Later, as the soundtrack I had Albert Ayler playing the 'Marseillaise'. It was a great little movie but I don't know what happened to it. - Paul McCartney

Brian Epstein's NEMS company had moved from Liverpool to London in 1963, establishing an office at 13 Monmouth Street in the centre of the capital.

In 1964 the company leased more offices at 5-6 Argyll Street, and gradually moved the operation to the new premises. On this day NEMS finally vacated 13 Monmouth Street.

The November 1966 issue of The Beatles Book Monthly featured an exclusive interview with Paul McCartney. Topics of conversation include the differences between their British and American albums, negotiations with Capitol Records, touring, songwriting, and the Revolver album.

First published in 1963 and continuing throughout their career and beyond, The Beatles Book Monthly was the official fanzine of the group. It took full advantage of having access to amazing rare photos, it featured exclusive articles, and contained insights not found anywhere else.

Sometimes also listed as Beatles Monthly Book, previously-owned copies of these excellent magazines continue to circulate in collector's circles, including online sites such as Ebay. While this UK-based fanzine had a rebirth in the late 70's and 80's, the most intriguing issues come from the years when the band was together.

It's so obvious why all the girls fall about at the thought of Paul McCartney, for when he puts on that impish grin and has that saucy look in his eyes, you can understand why all his fans want to smother him with kisses. But, not being one of the masses, I did what no other girl in her right mind would do whilst staring across the table into Paul's large brown eyes -- I took out my notebook and pen and proceeded to interview him.

As so many American fans had written-in asking why the Beatles' American LPs weren't nearly as good as the British ones, I asked Paul why their American albums feature as many as six instrumentals and only three new tracks, and why the rest of the tracks are made up of previous singles.

"Actually," said Paul, "It's not as bad as it seems. We're told that they like to have our singles on the LPs, and there's more demand for singles over there... about two to our one."

"We've argued this out with our record company, but they say it won't work if we release the same LPs over there because their selling is different. We've tried to compromise and asked if they would at least make the cover of the albums the same, but no deal."

"We also asked them to release fourteen tracks instead of twelve, but we were told that we'd lose the royalties on the extra two tracks, because apparently (in the United States) the royalties stay the same for six or eight tracks and also for twelve or fourteen."

"We wouldn't mind if we lost the royalties, but the publishers have to be paid, and someone's got to lay out the extra money for them. So we'd have to compromise and lose the royalties to make better (American) LPs... but I think we're beginning to get more control now."

I then asked Paul why their American record company releases more single than we do.

"Well, when we send the tapes over to the States, there are always two or three spare tracks, so they put them out as singles."

What did he think of the knockers who said that the Beatles weren't giving the public enough?

"We never expect to be knocked because we feel harmless. We don't want to offend, but we can't please everyone, and anyway, they'd get sick of us if we performed up and down the country the whole time."

I asked Paul if it was just because they'd made enough money, and therefore didn't need to keep up the personal appearances.

"Not really. It's a bit of everything -- over-exposure, laziness, and tax problems. You see, if we wanted to be the Beatles forever, then we'd have to become like Sinatra and take dancing lessons and acting lessons, and just be all-round entertainers... you know, get slicker. It's their whole life to other artistes, but we'd be kidding if we said that."

"It would have been different if we'd been struggling, but we made it so quickly and achieved a life-long ambition. Being a Beatle is not that big a part of life. There's lots more things for us to do. Take touring for example. We'd hate to be touring when we're thiry-five because we'd look silly. Anyway we'll probably be bald when we're thirty. Can't you see it... they'll be asking us to shake our hair, and we'd have to say 'We can't because we've got a bald patch.' Everyone has to get old. It's just that a lot of people don't adapt themselves and do exactly the same as they did at twenty, even though they are about forty."

On the subject of touring, I asked Paul whether or not they'd be doing a British tour. "I don't think we've really thought about not doing a tour in Britain this year." "You don't really miss touring. You get to rely a lot on your audience for your act, which means that when you perform live it's difficult to keep control of what's going on. I still get the same feeling as we had in the beginning. It's not quite as exciting doing a tour here as when we first started. But in a way it's the same. You still get rough nights with the good ones."

I asked Paul if he ever worried about not being able to come up with new material.

"No. I used to think that, and was frightened that I was going to dry up, but now I realize that it won't happen if you're interested. Our songs are always changing. But you still get the type of person who sticks to something even if they don't like it... Everyone can do something else... even a bank clerk or a labourer. I get annoyed with people who are too nervous to change their way of life."

"People say 'Yesterday' was my greatest piece of work, but I hope I will write a better one."

I asked him what had happened to the Beatles' plans to record in the States.

"Well, as I said before, we wanted to record some tracks for 'Revolver' in Memphis, but it all fell through for various reasons when Brian (Epstein) went over there to check up. We did go into the matter again when we were on our last American tour, but we found that the idea was going to prove very expensive and, as we didn't like being taken for a ride just because we're Beatles, we dropped it."

"One of the reasons why we wanted to try doing some recording in the states is that we have heard so much about the different sound they get. I think that 'Revolver' did produce a new sound anyway. Perhaps by accident, perhaps not. We have been looking for it a long time, and something was definitely there. We'd still like to record in the states, but I can't see it happening in the near future."

I finally asked Paul what he thought of their old hits -- do they sound old fashioned?

"Yes. They're a step back in time, and as for performing them on stage I don't think our audience would like it... but that of course depends on where we're playing. Germany, for example, cried out for the old hits because that is what they remembered us for."

What did he think of the knockers who said that the Beatles weren't giving the public enough?

"We never expect to be knocked because we feel harmless. We don't want to offend, but we can't please everyone, and anyway, they'd get sick of us if we performed up and down the country the whole time."

I asked Paul if it was just because they'd made enough money, and therefore didn't need to keep up the personal appearances.

"Not really. It's a bit of everything -- over-exposure, laziness, and tax problems. You see, if we wanted to be the Beatles forever, then we'd have to become like Sinatra and take dancing lessons and acting lessons, and just be all-round entertainers... you know, get slicker. It's their whole life to other artistes, but we'd be kidding if we said that."

"It would have been different if we'd been struggling, but we made it so quickly and achieved a life-long ambition. Being a Beatle is not that big a part of life. There's lots more things for us to do. Take touring for example. We'd hate to be touring when we're thiry-five because we'd look silly. Anyway we'll probably be bald when we're thirty. Can't you see it... they'll be asking us to shake our hair, and we'd have to say 'We can't because we've got a bald patch.' Everyone has to get old. It's just that a lot of people don't adapt themselves and do exactly the same as they did at twenty, even though they are about forty."

On the subject of touring, I asked Paul whether or not they'd be doing a British tour. "I don't think we've really thought about not doing a tour in Britain this year." "You don't really miss touring. You get to rely a lot on your audience for your act, which means that when you perform live it's difficult to keep control of what's going on. I still get the same feeling as we had in the beginning. It's not quite as exciting doing a tour here as when we first started. But in a way it's the same. You still get rough nights with the good ones."

I asked Paul if he ever worried about not being able to come up with new material.

"No. I used to think that, and was frightened that I was going to dry up, but now I realize that it won't happen if you're interested. Our songs are always changing. But you still get the type of person who sticks to something even if they don't like it... Everyone can do something else... even a bank clerk or a labourer. I get annoyed with people who are too nervous to change their way of life."

"People say 'Yesterday' was my greatest piece of work, but I hope I will write a better one."

I asked him what had happened to the Beatles' plans to record in the States.

"Well, as I said before, we wanted to record some tracks for 'Revolver' in Memphis, but it all fell through for various reasons when Brian (Epstein) went over there to check up. We did go into the matter again when we were on our last American tour, but we found that the idea was going to prove very expensive and, as we didn't like being taken for a ride just because we're Beatles, we dropped it."

"One of the reasons why we wanted to try doing some recording in the states is that we have heard so much about the different sound they get. I think that 'Revolver' did produce a new sound anyway. Perhaps by accident, perhaps not. We have been looking for it a long time, and something was definitely there. We'd still like to record in the states, but I can't see it happening in the near future."

I finally asked Paul what he thought of their old hits -- do they sound old fashioned?

"Yes. They're a step back in time, and as for performing them on stage I don't think our audience would like it... but that of course depends on where we're playing. Germany, for example, cried out for the old hits because that is what they remembered us for."

John, Paul, George & Ringo figuring out what's next